In March 2024, the world learned that Paul Alexander—the last person known to live full‑time in an iron lung—had died at age 78. His story, along with the recent surge of interest sparked by YouTuber Markiplier’s upcoming horror film Iron Lung, has thrust this nearly‑forgotten medical device back into the spotlight. But what exactly is an iron lung, how does it work, and why did it once represent the difference between life and death for thousands of people? This is the story of a machine that not only saved lives during the darkest days of polio but also laid the foundation for modern intensive care.

What Is an Iron Lung and How Does It Actually Work?

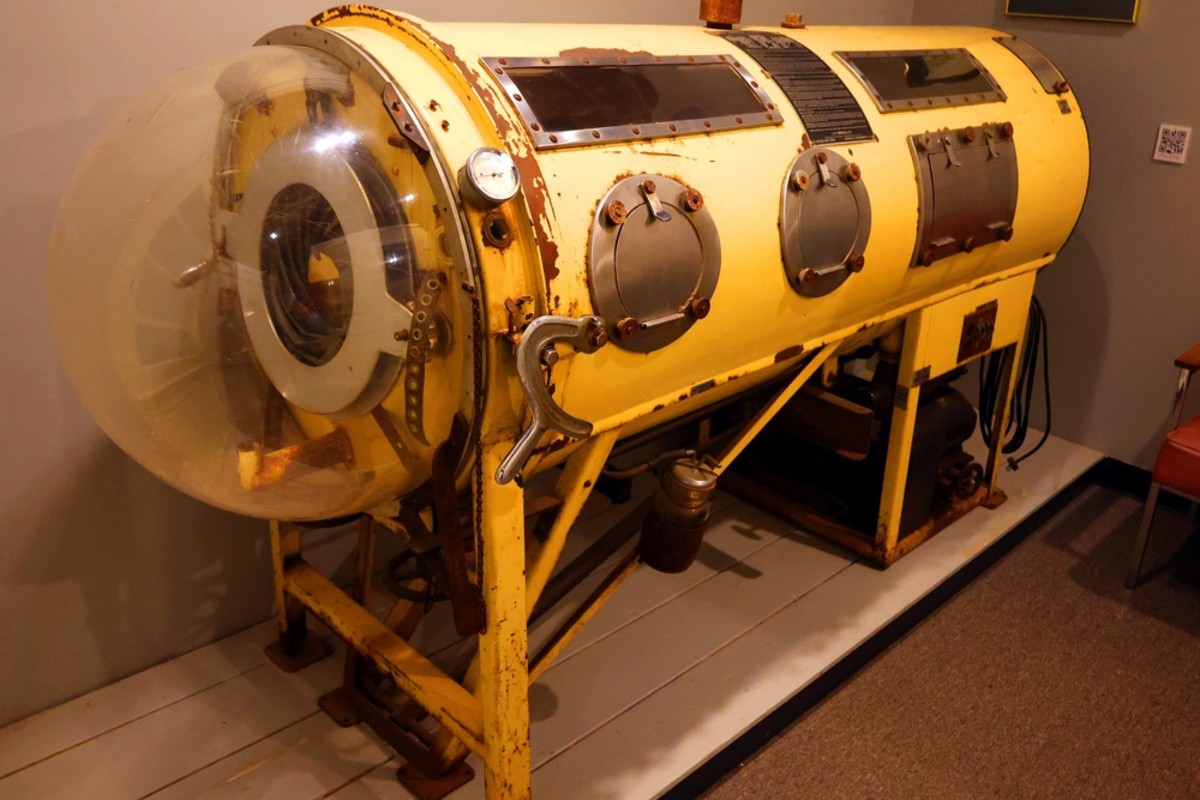

An iron lung is a type of negative‑pressure ventilator—a large, sealed metal cylinder that encloses a patient’s body up to the neck. Unlike today’s ventilators, which force air into the lungs (positive‑pressure ventilation), the iron lung works by mimicking the natural breathing mechanism. Here’s how it operates: the patient lies on a bed inside the airtight chamber, with their head protruding through a rubber‑sealed collar. An electric motor drives a bellows or pump that periodically sucks air out of the cylinder, creating a partial vacuum around the patient’s chest. This drop in external pressure causes the chest wall to expand, pulling air into the lungs through the nose and mouth. When air is allowed back into the chamber, the chest relaxes and the patient exhales. In effect, the machine “breathes” for the person, taking over when polio or other conditions paralyze the respiratory muscles.

From Harvard Labs to Polio Wards: The Invention That Changed Medicine

The iron lung was invented in 1927 by Philip Drinker and Louis Agassiz Shaw at the Harvard School of Public Health. Originally conceived as a way to treat coal‑gas poisoning, the duo realized their “cabinet respirator” could sustain polio victims whose chest muscles were paralyzed. The first clinical use came in 1928, when the device saved the life of an eight‑year‑old girl struggling to breathe. By the 1930s, mass production began, and during the polio epidemics of the 1940s and 1950s, iron lungs became a common sight in hospital wards. At the peak of the polio crisis, about 1,200 Americans relied on the machines. Each unit cost between $1,500 and $2,000—roughly the price of a house at the time—and weighed up to 500 pounds, making distribution a logistical challenge. Yet for thousands of patients, mostly children, the iron lung was the only thing standing between them and suffocation.

The Rise and Fall of the Iron Lung: A Timeline of a Medical Lifeline

1927 – Philip Drinker and Louis Agassiz Shaw patent the first practical “iron lung” at Harvard.

1928 – The device is used successfully on a young polio patient, proving its life‑saving potential.

1930s – Mass production begins; iron lungs are shipped to hospitals across the United States and abroad.

1940s‑1950s – Polio epidemics sweep the globe; iron‑lung wards become a haunting symbol of the disease.

1955 – Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine is introduced, drastically reducing new cases of paralytic polio.

Late 1950s – Positive‑pressure ventilators (the modern “ventilators” we know today) start to replace iron lungs.

2024 – Paul Alexander, the last full‑time iron‑lung user, dies in March, marking the end of an era.

2026 – Markiplier’s film Iron Lung brings the device back into popular culture, sparking renewed curiosity about its history and mechanics.

Why the Iron Lung Still Matters: Its Legacy in Modern Medicine

Although the iron lung is now a relic, its impact on medical technology is profound. It was the first device to provide long‑term mechanical ventilation, demonstrating that patients with paralyzed respiratory muscles could be kept alive for weeks, months, or even decades. This concept directly led to the creation of the intensive care unit (ICU). Moreover, the iron lung’s negative‑pressure principle offered a more natural breathing pattern than positive‑pressure ventilators, which can damage lung tissue over time. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, some engineers revisited negative‑pressure designs as a less invasive alternative to intubation. Today’s portable non‑invasive ventilators, such as BiPAP machines, owe a conceptual debt to the iron lung’s gentle, cyclical approach to supporting breath.

Where Things Stand Now: The Last Iron Lung Patients and Modern Replacements

With the global eradication of polio nearly achieved—only a handful of cases were reported in 2023—the need for iron lungs has virtually disappeared. Most of the few remaining users have switched to modern positive‑pressure ventilators or learned breathing techniques that allow them to spend part of the day outside the machine. Paul Alexander, for instance, used a portable ventilator for short periods but returned to his iron lung for most of his 72‑year confinement. Maintaining these antique devices is a growing challenge; replacement parts are scarce, and few technicians remember how to repair them. Yet some patients still prefer the iron lung’s comfort and reliability, a testament to the durability of Drinker and Shaw’s nearly‑century‑old design.

What’s Next for Respiratory Therapy and the Memory of the Iron Lung

As polio fades into history, the iron lung will likely become a museum piece—but its lessons endure. Researchers continue to explore negative‑pressure ventilation for certain respiratory conditions, and the device’s story serves as a powerful reminder of how innovation can emerge from crisis. Meanwhile, the cultural fascination with the iron lung is experiencing a revival, thanks in part to Markiplier’s upcoming film. This renewed attention offers an opportunity to educate a new generation about a technology that once represented hope for thousands of families. The iron lung may no longer be in hospitals, but its legacy—as a medical breakthrough, a lifeline during epidemic terror, and a stepping stone to modern critical care—will continue to breathe life into medical history.

The Bottom Line: Key Takeaways About the Iron Lung

• The iron lung is a negative‑pressure ventilator that encloses the patient’s body and uses air‑pressure changes to simulate natural breathing.

• Invented in 1927, it saved thousands of lives during the polio epidemics before the vaccine arrived in 1955.

• Paul Alexander, the last known full‑time user, lived in an iron lung for 72 years until his death in March 2024.

• The device paved the way for modern ICUs and inspired later, less invasive respiratory technologies.

• While obsolete in clinical practice, the iron lung remains a powerful symbol of medical ingenuity in the face of epidemic disease.