Measles, a highly contagious viral disease once common in childhood, has made a troubling resurgence in recent years despite being preventable by vaccination. With outbreaks occurring across the United States and globally, understanding this serious illness has never been more important. Measles can lead to severe complications, including pneumonia, brain inflammation, and even death, particularly in young children and immunocompromised individuals.

What Is Measles: Understanding the Highly Contagious Virus

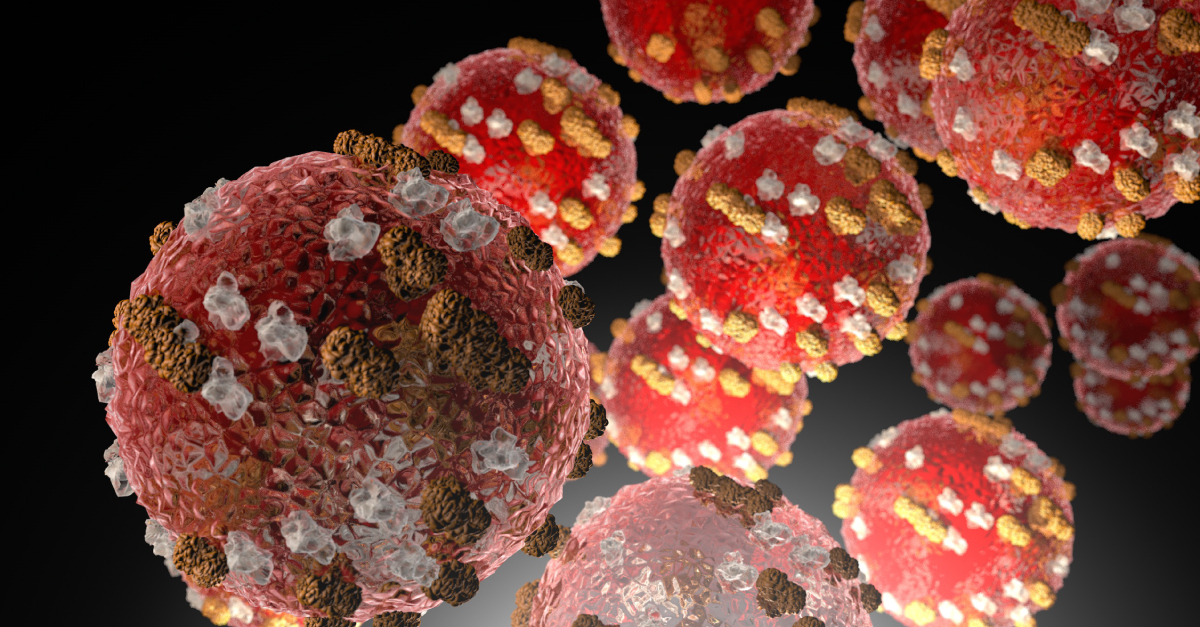

Measles, also known as rubeola, is caused by the measles virus, a member of the paramyxovirus family. The disease was once a common childhood infection worldwide before the introduction of vaccines in the 1960s. According to the World Health Organization, measles remains one of the world's most contagious diseases, with the virus capable of surviving in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours after an infected person leaves the area.

Before widespread vaccination, major measles epidemics occurred every two to three years, causing an estimated 2.6 million deaths annually. While vaccination has dramatically reduced cases, the WHO reports that measles still caused an estimated 95,000 deaths globally in 2024, mostly among unvaccinated or under‑vaccinated children under five years old.

How Measles Spreads: The Airborne Transmission That Makes It So Contagious

Measles is transmitted through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks. The CDC notes that the virus can also spread by direct contact with infected nasal or throat secretions. What makes measles exceptionally contagious is that the virus remains active and infectious in the air for up to two hours, meaning people can become infected simply by entering a room where someone with measles has been.

"Measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases," explains Dr. Bill Moss of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. "In a completely susceptible population, one person with measles will infect an average of 12–18 other people." This level of contagiousness means that if one person has measles, up to 90% of nearby people who are not immune will likely become infected.

An infected person can spread measles from four days before the rash appears through four days after the rash erupts. This means transmission can occur before a person even knows they have the disease, making containment challenging during outbreaks.

From Fever to Rash: The Measles Symptom Timeline

Measles symptoms typically appear 7 to 14 days after exposure to the virus. The illness usually begins with:

- High fever – May spike to 104–105°F (40–40.6°C)

- Dry cough

- Runny nose (coryza)

- Red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis)

About 2–3 days after these initial symptoms, tiny white spots called Koplik spots may appear inside the mouth on the inner cheeks. These spots are a distinctive sign of measles. Then, 3–5 days after symptoms begin, the characteristic measles rash develops.

The rash usually starts on the face and behind the ears, then spreads down the body to the chest, back, arms, and legs. It consists of flat red spots that may blend together as they spread. The rash typically lasts 5–6 days before fading, with the fever usually subsiding as the rash appears.

Why Measles Is Dangerous: Serious Health Complications

While many people think of measles as just a rash and fever, the disease can lead to severe, sometimes life‑threatening complications. According to the Mayo Clinic, common complications include:

- Pneumonia – The most common cause of death from measles

- Encephalitis – Brain swelling that occurs in about 1 in 1,000 cases and can cause permanent brain damage

- Severe diarrhea and dehydration

- Ear infections that can lead to permanent hearing loss

- Pregnancy complications including miscarriage, premature birth, or low birth weight

- Blindness from corneal scarring, particularly in children with vitamin A deficiency

Perhaps most concerning is measles' effect on the immune system. Research shows that measles can "wipe out" the immune system's memory of previous infections, leaving children vulnerable to other diseases they had already fought off. This immune amnesia can last for months or even years after measles infection.

"About 1 in 5 unvaccinated people in the U.S. will require hospitalization from measles," notes Johns Hopkins experts. "In 2024, that rate was even higher—about 40% of people with measles were hospitalized."

The Power of Vaccination: How the MMR Shot Protects Communities

The measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine is the most effective way to prevent measles. According to CDC data, two doses of the MMR vaccine are about 97% effective at preventing measles. The vaccine schedule in the United States recommends:

- First dose: 12–15 months of age

- Second dose: 4–6 years of age (before kindergarten entry)

The MMR vaccine is safe and has been extensively studied. Numerous scientific studies have found no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Mild side effects may include soreness at the injection site, low fever, or a mild rash, but serious reactions are extremely rare.

"The risks of severe illness, death, or lifelong complications from measles infection far outweigh the generally mild side effects some people experience following vaccination," emphasizes the Johns Hopkins article. "Serious reactions to the MMR vaccine are rare."

For communities to be protected against measles outbreaks, at least 95% of the population needs to be vaccinated—a concept known as herd immunity. This protects those who cannot receive the vaccine, including infants under 12 months, pregnant people, and those with certain medical conditions or compromised immune systems.

Measles Today: Recent Outbreaks and Vaccination Challenges

Despite being declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, measles has made a comeback in recent years due to declining vaccination rates. In 2025, the U.S. experienced significant outbreaks in Texas and New Mexico, with hundreds of cases reported and the first measles death in the country since 2015.

Globally, the WHO reports that measles cases continue to rise in many regions. Ten countries in the Americas reported measles outbreaks in 2025 alone. The decline in vaccination coverage during the COVID‑19 pandemic has contributed to this resurgence, with an estimated 30 million infants under‑protected against measles in 2024.

Public health officials emphasize that maintaining high vaccination rates is crucial to preventing future outbreaks. "Because measles is so contagious, it relies on at least 95% of a community to be vaccinated," explains Dr. Moss. "In the U.S., about 91% of U.S. children ages 19–35 months have been vaccinated. However, coverage in some communities is much lower, putting them at greatest risk."

Key Facts About Measles Everyone Should Know

- Measles is one of the world's most contagious diseases—more contagious than COVID‑19 or influenza.

- The virus can live in the air for up to two hours after an infected person leaves the area.

- Symptoms appear 7–14 days after exposure and include high fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes, and a distinctive rash.

- Complications can be severe and include pneumonia, brain swelling, blindness, and death.

- Two doses of the MMR vaccine are about 97% effective at preventing measles.

- Vaccination not only protects individuals but also creates herd immunity to protect those who cannot be vaccinated.

- Before the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, major epidemics caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year.

- Measles vaccination prevented an estimated 59 million deaths between 2000 and 2024.

Understanding measles—how it spreads, its symptoms, and the critical importance of vaccination—is essential for protecting individual and community health. With accurate information and timely vaccination, we can work toward a future where this preventable disease no longer threatens children and families worldwide.